Why We Need to Protect the Extinct Woolly Mammoth | A CITIES Conference Update

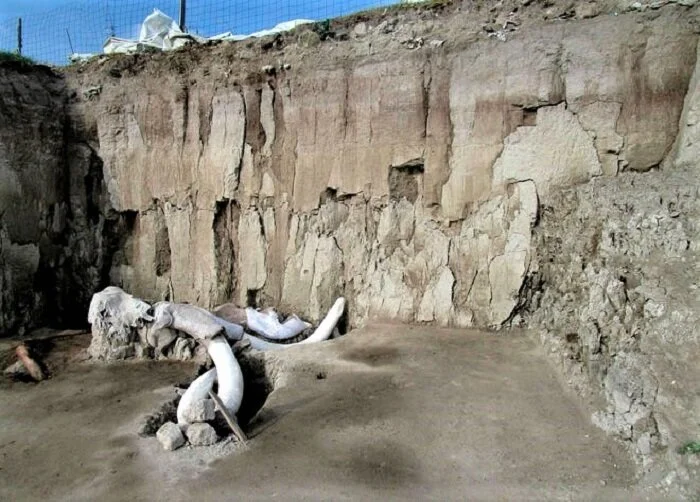

/Two mammoth skeletal mounts on exhibit at the French National Museum of Natural History in Paris: a southern mammoth , Mammuthus meridionalis, and a woolly mammoth ( Mammuthus primigenius ). via Wiki commons by Ghedo.

By Zara Bending, Associate, Centre for Environmental Law, Macquarie University. First published on The Conversation.

An audacious world-first proposal to protect an extinct species was debated on the global stage last week.

The plan to regulate the trade of woolly mammoth ivory was proposed, but ultimately withdrawn from an international conference on the trade of endangered species.

Instead, delegates agreed to consider the question again in three years, after a study of the effect of the mammoth ivory trade on global ivory markets.

Why protect an extinct species?

The Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) is an international agreement regulating trade in endangered wildlife, signed by 183 countries. Every three years the signatories meet to discuss levels of protection for trade in various animals and their body parts.

The most audacious proposal at this year’s conference, which concluded yesterday in Geneva, was Israel’s suggestion to list the Woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) as a protected species.

Specifically, it aimed to list the woolly mammoth in accordance with the Convention’s “lookalike” provision. Once woolly mammoth ivory is carved into small pieces, it is indistinguishable from elephant ivory without a microscope. The proposal is designed to protect living elephants, by preventing “laundering” or mislabelling of illegal elephant ivory.

Had it passed, it would have been the first time an extinct species has been listed to save its modern-day cousins. Most populations of woolly mammoths went extinct after the last ice age, 10,000-40,000 years ago.

The Venus of Brassempouy (French: la Dame de Brassempouy, meaning "Lady of Brassempouy", or Dame à la Capuche, "Lady with the Hood") is a fragmentary ivory figurine. It was discovered in a cave at Brassempouy, France in 1892. About 25,000 years old, it is one of the earliest known realistic representations of a human face. The Venus of Brassempouy was carved from mammoth ivory. via Wikipedia France.

Wait, you can trade mammoth ivory?

The trade in woolly mammoth tusks lies at the convergence of Earth’s environmental crises.

As the climate crisis melts permafrost in the Siberian tundra, preserved mammoths bearing tusks as large as 4.2m long (weighing as much as 84kg) have been unearthed for the first time in millennia.

International trade in mammoth ivory is not illegal (except for import to India under domestic legislation), and the domestic trade of Woolly mammoth ivory is not banned by most countries.

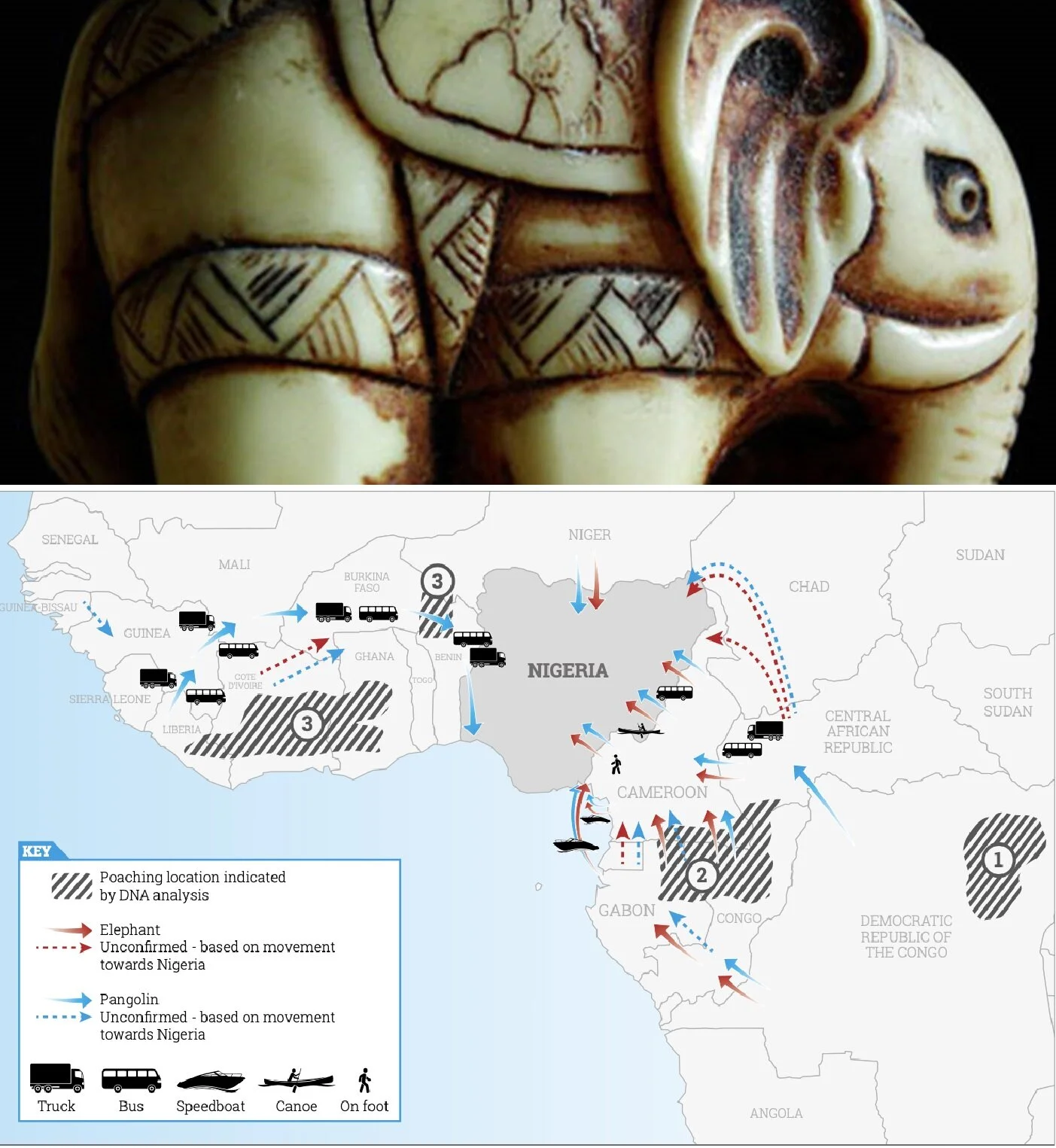

While poorly documented, the main trade route for tusks is thought to be from Russia to Hong Kong and then mainland China for processing.

Imports to Hong Kong have increased dramatically from fewer than 9 tonnes per year from 2000 to 2003 to an average of 31 tonnes per year from 2007 to 2013. Similarly, one survey found a fourfold increase in mammoth ivory sales in Macau between 2004 and 2015.

Ubsunur Hollow Biosphere Reserve located on the border of Mongolia and the Republic of Tuva is one of the last remnants of the mammoth steppe[1] via Wikipedia.

It’s not all mammoth

While some of this mammoth trade is legitimate, plenty of traders are passing elephant ivory off as mammoth. Research has found that, while it’s very hard to tell how much of the legal mammoth trade is actually (illegal) elephant ivory, tighter regulation may reduce opportunities for the laundering of elephant ivory.

The proposal would not ban trade altogether, but would require an exporting country to prove that specimens are mammoth ivory to get a permit.

Ivory laundering goes the other way as well. Grade A mammoth ivory can be carved and passed off as elephant ivory trinkets and enter the illegal wildlife trade.

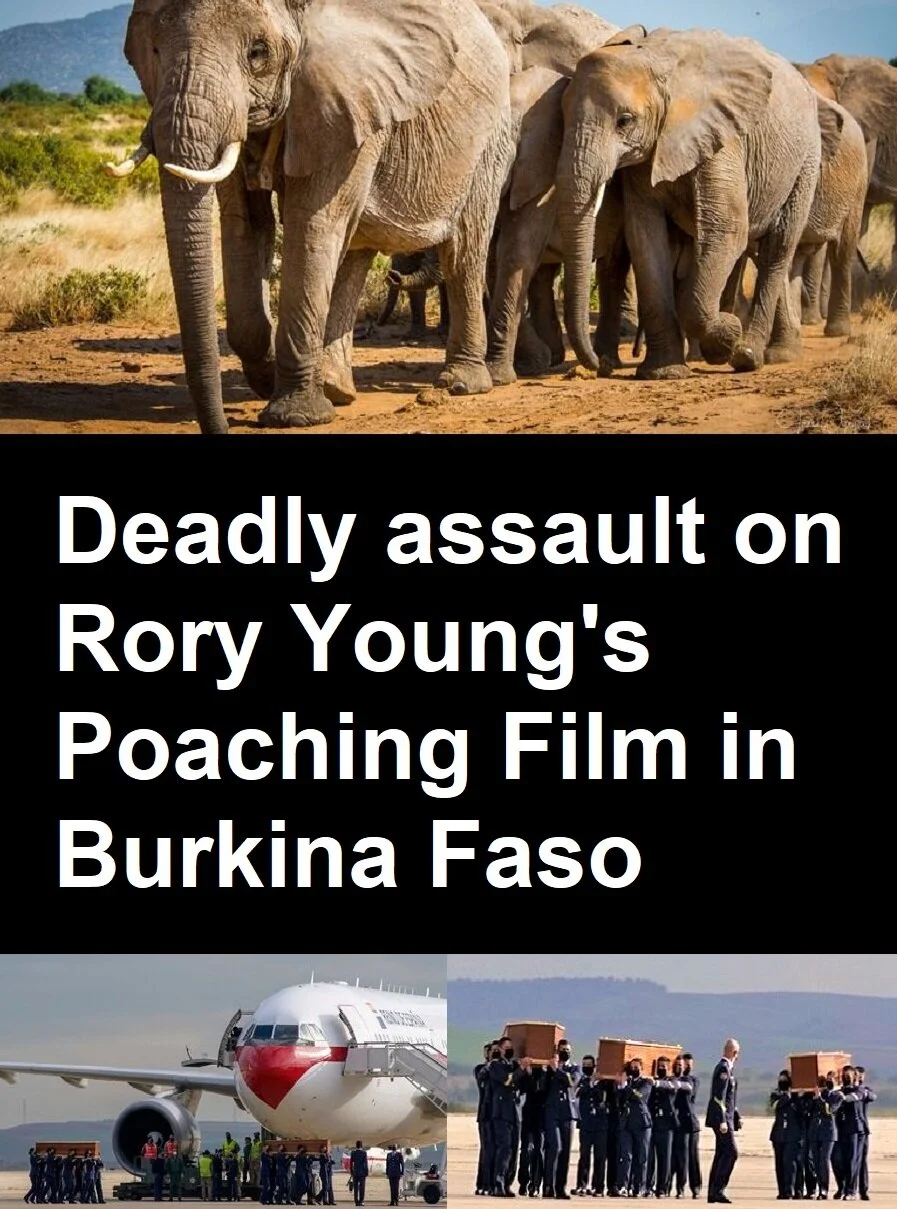

The illegal wildlife trade claims the lives of 20,000-50,000 elephants annually and is the second greatest direct threat to species survival.

Is it woolly thinking?

The new proposal was not without its detractors. Some “ice ivory” sellers and carvers argue mammoth ivory should be promoted as an alternative to elephant ivory to meet market demand without poaching. Others maintain extinct species should be regulated by the laws and codes observed by the global antiquities trade.

While Israel has not taken positions on these points, the move would be in line with other global efforts to stem the tide of organised crime syndicates profiting from the illegal wildlife trade.

My own research, along with government inquiries around the world, has found legal markets in ivory, regardless of origin, can and will be exploited as conduits for illegal trade.

Further, a recent analysis of the global online antiquities market found dealers and buyers have resoundingly poor legal literacy. Ethical dealer behaviour is highly inconsistent.

A solution put on ice

If it had passed, this proposal would have been a landmark achievement in the protection of elephants. Instead, Israel’s delegates ultimately withdrew the motion, in the face of vehement opposition from Russia, which is the primary exporter of mammoth ivory.

Delegates from Canada, the United States of America and the European Union said there was insufficient evidence to support the change. The various parties agreed to support a study into the mammoth ivory trade as a compromise, and Israeli delegates are hopeful the findings will reopen discussion at the next conference, three years from now.

![Into-the-Okavango_[Neil-Gelinas]_3-dbl.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55f45174e4b0fb5d95b07f39/1561937163642-AJXZW3I471QGTYL0AE03/Into-the-Okavango_%5BNeil-Gelinas%5D_3-dbl.jpg)