Our Story 2-22-1898: Frazier B. Baker and Baby Julia Fatally Shot for Being a Post Master in Lake City, S.C.

/Anne of Carversville has been been committed to telling America’s stories since 2007. This is the first of many new stories we will tell, so our American history is not erased by Maga voters seeking to pretend that none of these events ever happened.

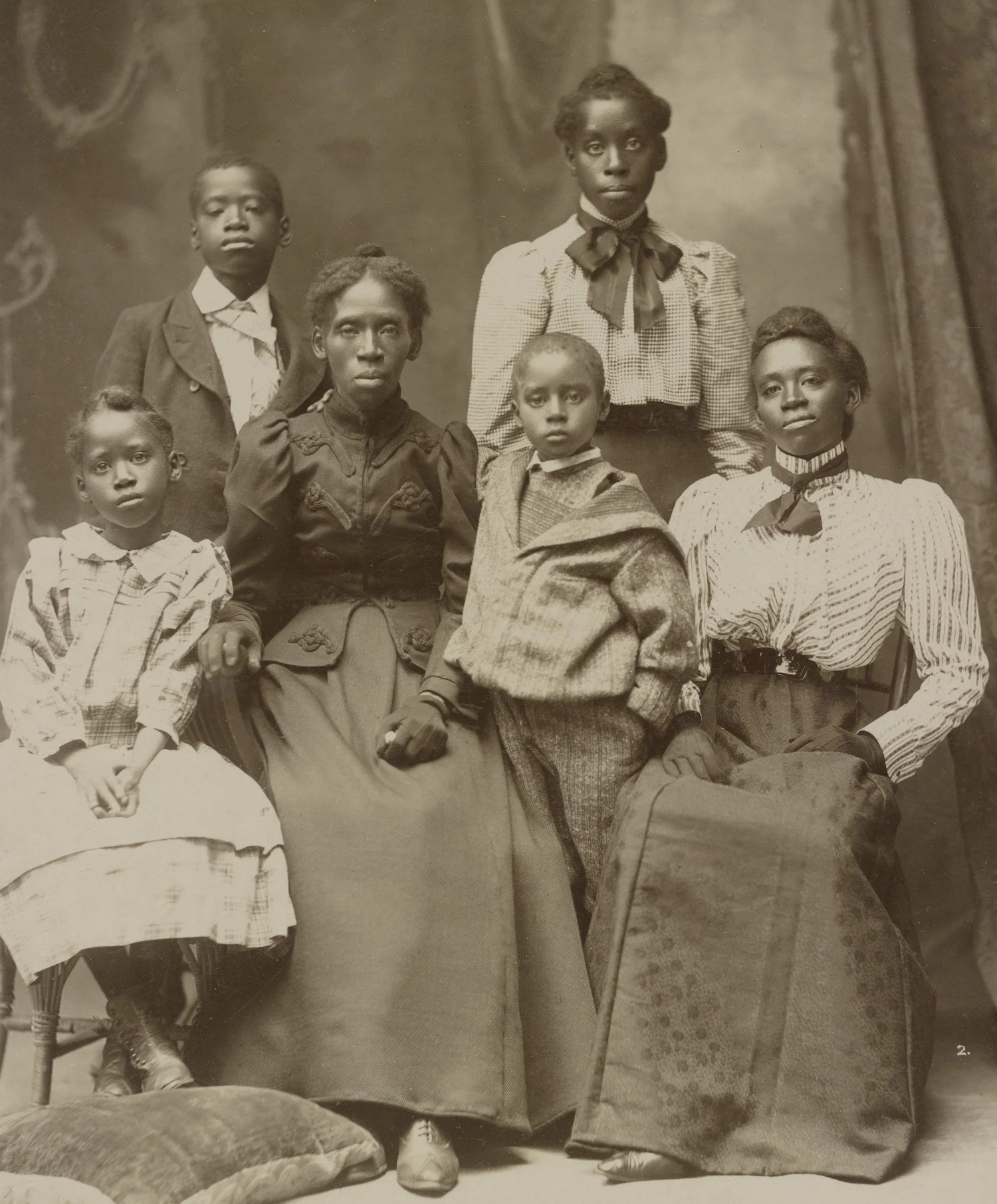

Frazier B. Baker, the first Black postmaster of the small town of Lake City, South Carolina, and his baby daughter, Julia, were killed on this day. Baker’s wife Lavinia and her five surviving children Lavinia wife and three other daughters were injured when a lynch mob attacked.

The 19th century brought enormous change in the postal workforce. In 1802, Congress banned African Americans from carrying U.S. Mail. This ban lasted to the late 1860s, when newly-enfranchised, post Civil War African Americans began receiving appointments as postmasters, clerks, and city letter carriers.

Reconstruction and Federal Jobs for Black Americans

As America advanced towards the 20th century, the political pendulum began to swing backwards, eliminating many gains of the immediate post-Civil War period. This period of American history is called ‘Reconstruction’ and it operated in 1865-1877.

Frazier Baker became a postmaster in 1897, appointed by President William McKinley after the 1896 presidential election. Local whites in Lake City, SC rejected his appointment and began to attack Baker’s abilities. They argued that contact between Black men and white women would be too easy at the post office.

Once already, whites had burned down the first post office, convinced this would end the postmaster career of Frazier Baker.

Postal inspectors determined the accusations of Baker’s professional skills were unfounded. The conclusion wasn’t accepted by hundreds of whites who set fire to the second post office, where the Bakers lived.

The conclusion wasn’t accepted by hundreds of whites who set fire to the second post office, where the Bakers lived after the first fire.

Lynching by Fire of Frazier Baker and Baby Julia

Documents say that more than 100 bullets were fired on the scene of the nightmare that engulphed Frazier Baker and his family in early morning of February 22, 1898.

The family fought frantically to put out the flames before opening the door of the house to flee. Facing the mob of white men, shots began with Frazier Baker falling first.

The barrage of gunfire continued unabated, and the three eldest Baker children were all seriously injured trying to escape to a neighbor’s house.

Mother Lavinia was the last going for the door, with Julia in her arms. A bullet ripped through Julia’s hand protecting Julia and killed her instantaneously. Struck in the leg by a second bullet, Lavinia Baker collapsed beside the burning building, as the mob dispersed.

As the last flames consumed the wooden post office structure, local African Americans offered sanctuary to the new widow and her five surviving children. Reports are that the survivors received no medical treatment for their wounds for over three days.

The Lake City Backlash

Outraged citizens in Lake City wrote a resolution describing the attack and 25 years of “lawlessness” and “bloody butchery” in the area.

Crusading journalist Ida B. Wells wrote the White House about the attack, noting that the family was now in the Black hospital in Charleston “and when they recover sufficiently to be discharged, they) have no dollar with which to buy food, shelter or raiment.”

President McKinley ordered an investigation that led to charges against 13 men, but no one was ever convicted for the viscious attack on the Baker family.

The family left South Carolina for Boston, and later that year, the first nationwide civil rights organization in the U.S., the National Afro-American Council, was formed.

In 2019, the Lake City post office was renamed to honor Frazier Baker. Bill H.R. 7230 (115th): To designate the facility of the United States Postal Service located at 226 West Main Street in Lake City, South Carolina, as the “Postmaster Frazier B. Baker Post Office” was introduced by prominent SC Congressman Jim Clyburn of the 6th District.

“We, as a family, are glad that the recognition of this painful event finally happened,” his great-niece, Dr. Fostenia Baker said. “It’s long overdue.”

Resources: African-American postal workers in the 20th century USPS