The Resilience of Barbados Counters Trump’s ‘Sh-thole’ Remarks

/File:Collectie Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen TM-60062020 Suikerrietoogst Barbados fotograaf niet bekend.jpg

By J.M. Opal, Associate Professor of History and Chair, History and Classical Studies, McGill University. First published on The Conversation.

In a recent interview with Vanity Fair, former attorney and future inmate Michael Cohen revealed some of the uglier things Donald Trump said to him during their many years together.

Among the alleged quotes: “Name one country run by a Black person that’s not a sh—hole.” (One wonders how Trump characterized the United States when Barack Obama was President.)

Rarely stated so bluntly, this racist trope is widespread. As always, Trump gives vulgar expression to quiet prejudice, making him sound “honest” to about 40 per cent of Americans no matter how many lies he tells. As Sarah Huckabee Sanders noted after a similar revelation last year, Trump’s straight-shooting bigotry is one thing his fans love about him.

Those who don’t love him need to fight back with specific examples from the real world. Time and again, we need to highlight the big, complex reality that Trump and many of his supporters call “fake news.” Otherwise, his twisted version of the truth will continue to displace objective reality.

Take the nation of Barbados, a small island on the eastern end of the Caribbean that I’ve been studying and teaching about for many years. Best known as the birthplace of Mount Gay rum and Rihanna, it’s a remarkable example of what some Black people endured and overcame in the New World.

Ground zero for slavery and racism

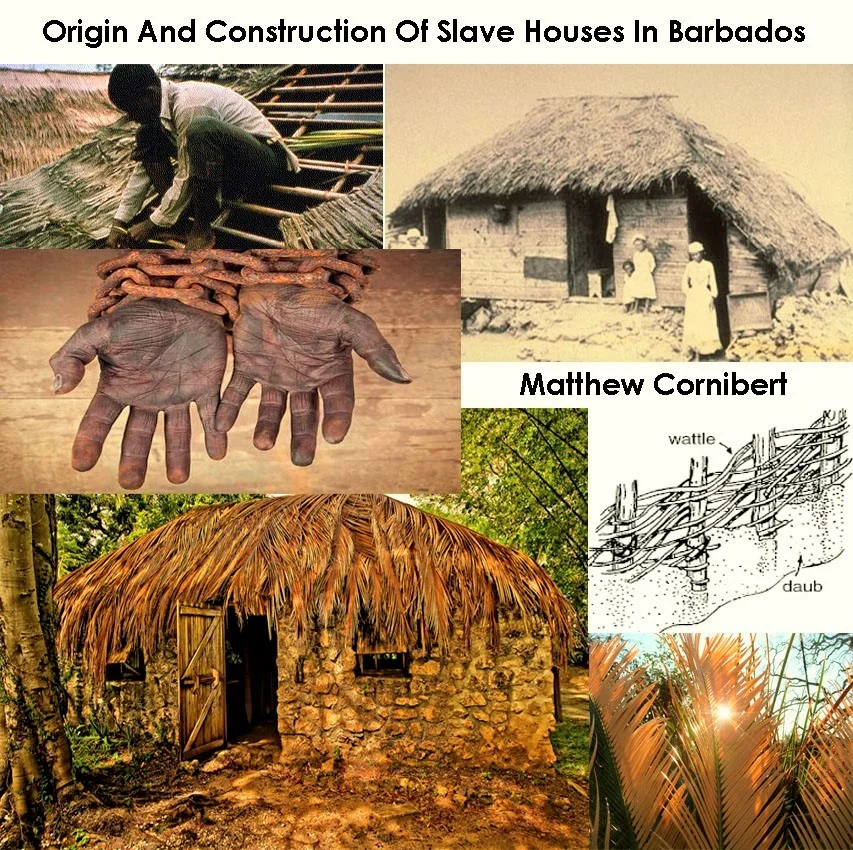

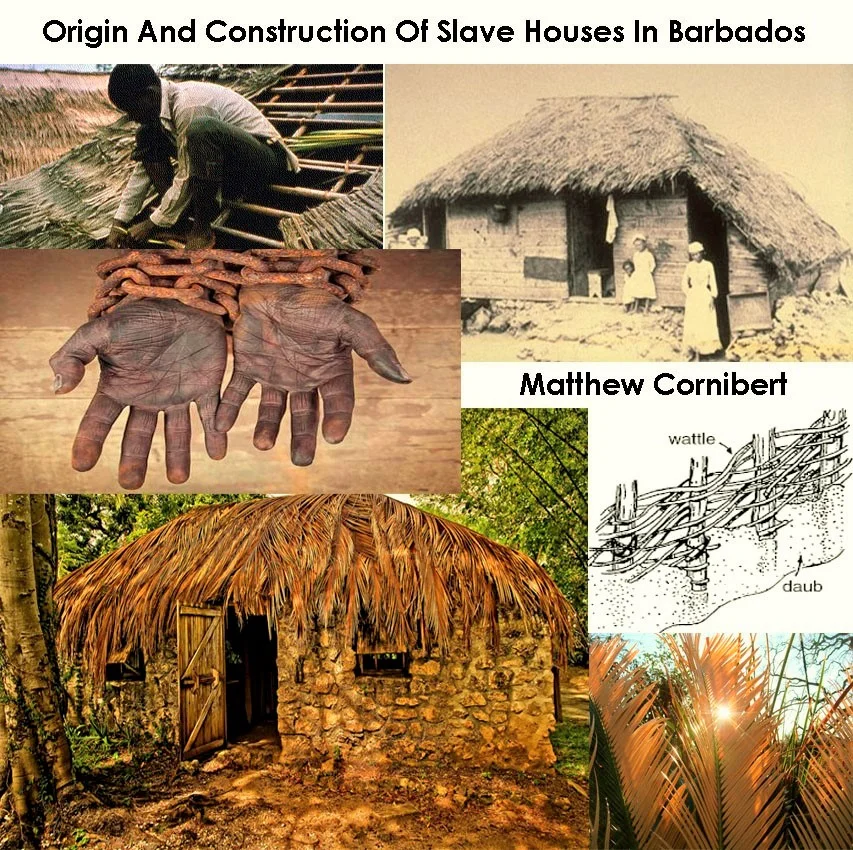

Settled by the English in 1627, Barbados became one of the most brutal and profitable slave regimes in human history. An astonishing 600,000 Africans came in chains to Barbados, about five per cent of all the victims of the Atlantic slave trade. Smaller numbers of Irish and Native American captives were also “Barbadoz’d,” exiled to this early jewel in the British crown.

Few of them survived for long.

The people spent their days under the tropical sun, cutting and dragging eight-foot canes to cattle-drawn sugar mills. There the stalks were crushed between heavy rollers and boiled in huge cauldrons. Many slaves had their hands caught in the rollers; others, exhausted by 24-hour shifts, fell into the cauldrons.

Dental records show that the Black majority nearly starved each winter, when food supplies were scarce. (Sugar monoculture left little room for corn, squash or yams.) Malnutrition led to frequent miscarriages and stillbirths. Babies crawled around in soils full of worms and tetanus, leading to catastrophic death rates for infants.

As early as 1661, well before Black slavery had taken hold in North America, the Barbados assembly passed a code describing all “negroes” as dangerous brutes, liable to the same kinds of discipline —branding, whipping, gelding —as livestock. This code was later adopted by the British colonies in Jamaica and South Carolina, and Barbadian slaves were sold to buyers as far away as Boston.

In 1692, the same year a Barbadian slave named Tituba began the Salem witch hysteria, the planters snuffed out an uprising among the slaves. The accused were castrated, burned alive or “hung out to dry” on meat hooks. For more than a century after that, a miserable calm settled over the island.

In short, Barbados was Ground Zero for American slavery and racism, a Caribbean concentration camp in which hundreds of thousands of people of African descent were tortured to make white planters very rich.

Transition to Peaceful Stability

No wonder those planters feared violent retribution when the British Empire abolished slavery in the 1830s, just as the “peculiar institution” took off again in the cotton-growing United States.

Instead, Barbados became one of the most peaceful and stable Caribbean islands.

Most “Bajans,” as the islanders are known, valued honest work, humility and forgiveness. Gradually and painfully, they wrested political power away from the old planter elite, forming strong unions during the Great Depression and finally breaking away from British rule in 1967.

Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley speaks during the opening plenary of the Global Action Climate Summit on Sept. 13, 2018, in San Francisco. (AP Photo/Eric Risberg)

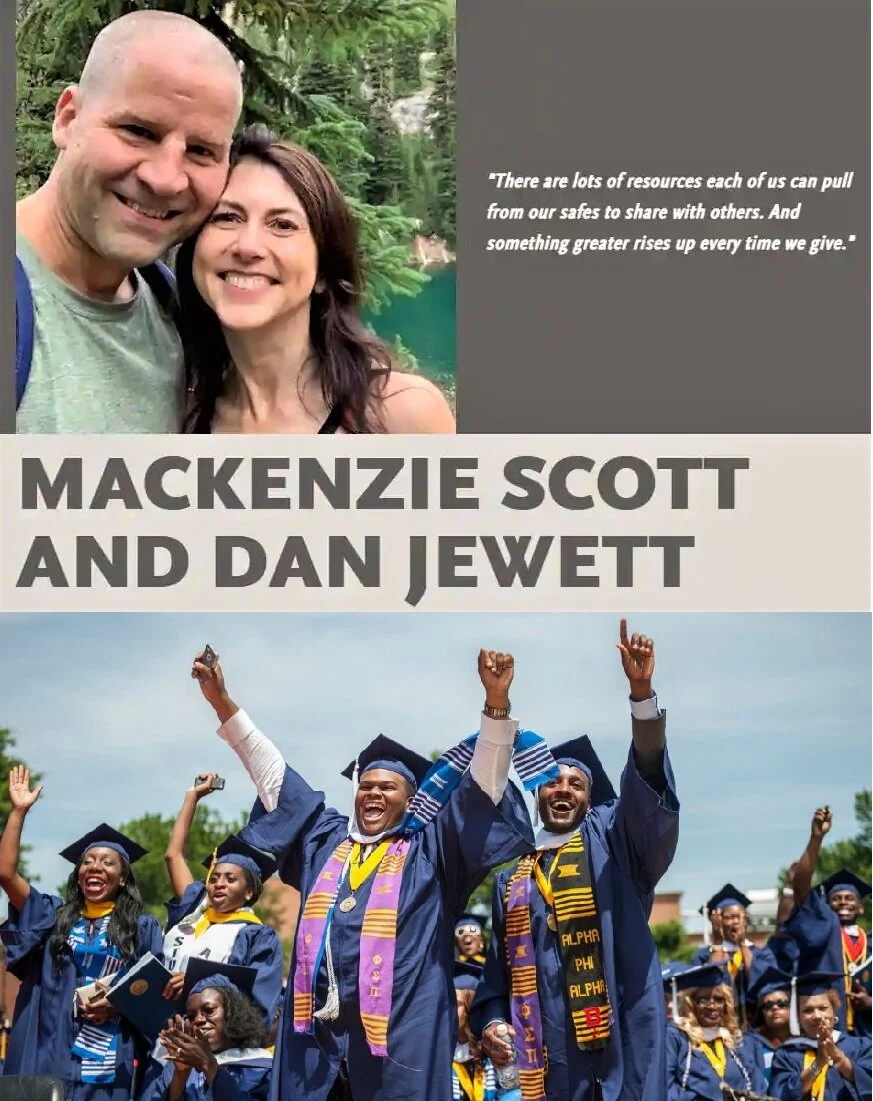

Today, Barbados is a democracy that combines British and Bajan traditions of parliamentary supremacy, the rule of law and social justice. Prime Minister Mia Mottley leads the Barbados Labour Party, which prevailed over the Democratic Labour Party in this spring’s elections. She is the first woman to serve as prime minister.

This is not to deny the nation’s many social problems, especially since the collapse of the sugar industry during the 1980s and because of the lingering effects of the 2008 financial crisis. Rather, it is to recognize Barbados as an example of human endurance and solidarity within a pitiless world.

So watch what you say about “sh—thole countries,” Mr. Trump. At the present hour, tiny Barbados inspires as much hope as the mighty United States.