Ghana’s Copyright Law for Folklore Hampers Cultural Growth

/The National Folklore Board (NFB) is warning all persons who use Ghana’s folklore outside the customary context and/or for commercial purposes that permission must be sought from its outfit for such usages.

In a release NFB said, folklore includes music, dance, art, designs, names, signs and symbols, performances, ceremonies, architectural forms, handicrafts and narratives, and any other literary, artistic and scientific expressions belonging to the cultural heritage of Ghana which are created, preserved and developed by ethnic communities of Ghana or an unidentified Ghanaian author.

Local usage of a work of folklore outside the customary context and/or for commercial purposes includes but is not limited to, the use of an Adinkra symbol for a company’s corporate branding and the use of other expressions of folklore for promotional and other commercial purposes. May 13, 2019 via Voyages Afriq

(Note from Anne: AOC has a more nuanced view of cultural appropriation than the blistering Twitter universe’s. I’m not such a fool as to try to make the case or ask questions in today’s environment. But AOC will share articles from others — representing all viewpoints — around this increasingly complex topic. I do note that even Dapper Dan agrees that the infamous Gucci ‘blackface’ sweater had nothing to do with blackface, a reality that we went to great lengths to discuss in an earlier article. On this subject, inquiring minds don’t really exist. But we will try to till the parched earth in hopes of one day seeing a small fertile mind grow.. . and then another . . . and another . . . into dialogue.)

By Stephen Collins, Lecturer, University of the West of Scotland. First published on The Conversation

Ghana has a rich folkloric tradition that includes Adinkra symbols, Kente cloth, traditional festivals, music and storytelling. Perhaps one of Ghana’s best known folk characters is Ananse, the spider god and trickster, after whom the Ghanaian storytelling tradition Anansesem is named.

Ghana also has some of the world’s most restrictive laws on the use of its folklore. The country’s 2005 Copyright Act defines folklore as “the literary, artistic and scientific expressions belonging to the cultural heritage of Ghana which are created, preserved and developed by ethnic communities of Ghana or by an unidentified Ghanaian author”.

This suggests that the legislation, which is an update of a 1985 law, applies equally to traditional works where the author is unknown and new works derived from folklore where the author is known.

The rights in these works are “vested in the President on behalf of and in trust for the people of the republic”. These rights are also deemed to exist in perpetuity. This means that works which qualify as folkloric will never fall into the public domain – and will never be free to use.

The 1985 Act only restricted use of Ghana’s folklore by foreigners. The 2005 Act extended this to Ghanaian nationals. In principle, this means that a Ghanaian artist wishing to use Ananse stories, or a musician who wants to rework old folk songs or musical rhythms must first seek approval from the National Folklore Board and pay an undisclosed fee.

This is deeply problematic. Following independence in 1957, many artists have explicitly and habitually drawn on Ghana’s folk traditions to develop today’s creative industries. The 2005 Act means that the current generation of cultural practitioners must either seek permission to use and rework their cultural heritage, or look elsewhere for inspiration.

There is clearly a balance to be struck between safeguarding and access when it comes to the protection of a state’s cultural heritage. However, it is important to acknowledge that while Ghana’s legislation appears to tip towards protection at the expense of access, it restricts growth in the creative industries by discouraging artists from engaging with their national cultural heritage.

Our cultural heritage: Ghana’s warmth and hospitality via Ghanaladies.com

History of protection

Ethnomusicologist and musician John Collins has noted that the development of the 2005 Act was partly in response to US singer Paul Simon’s use of a melody taken from the song ‘Yaa Amponsah’ for his 1990 album 'The Rhythm of the Saints’.

Simon attributed this melody to the Ghanaian musician Jacob Sam and his band the Kumasi Trio. But on further investigation the Ghanaian government asserted that the melody was a work of folklore and so, belonged to the state.

From this, two things are clear. Firstly, in Ghana folklore belongs to the state and not the originating communities that predate the modern state. Secondly, Jacob Sam received no recompense for Simon’s use of the work, with all royalties owed on the work flowing back the government.

There are a number of issues here that set Ghana apart from other African states.

Many states allow for the use of folklore by nationals and if a fee is applicable then it is paid as a royalty based on revenue raised. This is the case in all three states bordering Ghana: Togo, Burkina Faso and Cote d’Ivoire. Consequently, if an artist in one of these countries reworks folklore but makes no money, then no money is paid for that use. If the work becomes successful then the artist and the rights holder benefit.

However, in Ghana, the law states that payment is paid prior to use and so prior to any profits made. This potentially adds to the cost of production and so discourages use of folklore.

The other issue here is who owns the rights in national heritage. In many countries, such as Kenya, the originating communities retain the rights to their expressions of cultural heritage.

However, in Ghana the rights are vested in the office of the president. This means that any moral or financial benefit that results from uses of folklore flow to the office of the president, rather than being used to support continued safeguarding and growth of cultural heritage within communities.

Guarding against exploitation

The Arts and Culture Company in partnership with the National Commission on Culture, Ghana Tourism Authority, National Folklore Board and Tourism Society of Ghana under the auspices of the Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture officially launched the GHANA ARTS AND CULTURE AWARDS on September 6, 2019 at the Accra Tourist Information Center and the event was being sponsored by GIHOC Distilleries Company Limited. via

Though Ghana’s present regime may appear draconian, there are compelling reasons why such protective measures are required.

Firstly, Ghana’s cultural heritage – its traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions – have been and continue to be exploited by non-Ghanaians in international markets with no beneficial interest flowing either to the state or to the originating community.

To give this some context, Simon’s use of Yaa Amponsah was only one use of Ghana’s cultural heritage in the developing of a new, and commercially successful, work. More recently, there were a number of press reports in Ghana that the Ghana Folklore Board intended to sue the producers of Marvel’s Black Panther for the unauthorised use of kente cloth in some of the characters’ costumes.

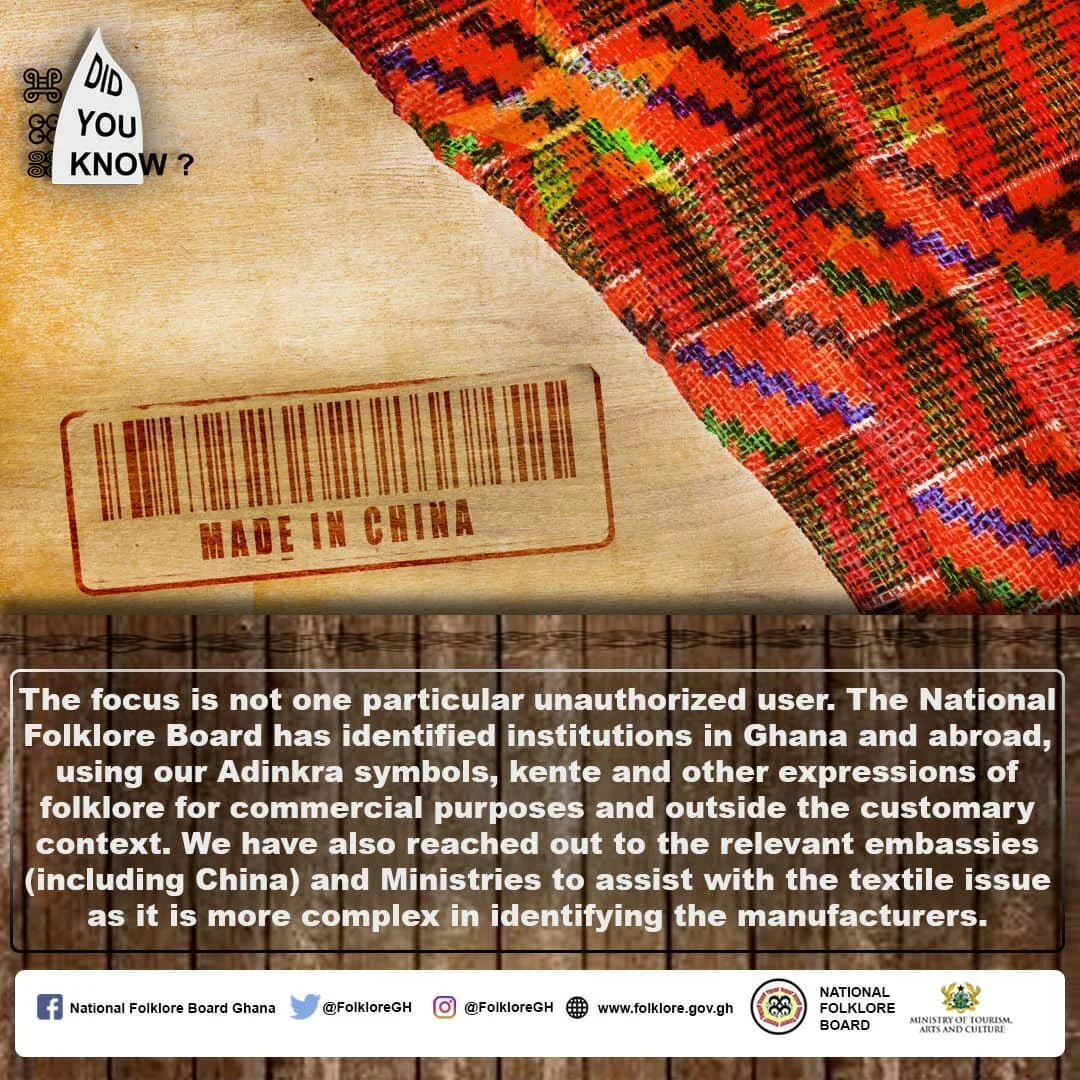

The Folklore Board clarified these reports in a press release, saying it did not intend to sue – but rather, wished to discuss attribution. Kente is specifically named as an object of protection under the 2005 Act and the current proliferation of unauthorised cheap kente designs entering global markets from China presents a significant challenge. Attribution, in this case, would ensure that cinema goers across the world would associate kente with Ghana, bringing a traditional craft to a global audience.

The board faces a particularly complex challenge. It must balance safeguarding traditional heritage with allowing creative artists room to reuse and rework elements of that heritage in a way that does not add to the cost or complexity of production.

Though the threat of unfair exploitation is real, equally real is the potential threat to the creative industries and the future development of Ghana’s living heritage if the country’s artists move away from their cultural heritage.

Related News on Cultural Appropriation

Dior Finally Says No to Sauvage: Why luxury fashion and cultural appropriation are on a collision course by Vanessa Friedman New York Times